Jonathan Fruchter

Virtual homological torsion in graphs of free groups with cyclic edge groups (j/w Dario Ascari)

Full paper available at arXiv:2505.20960

Extended abstract to accompany a poster presented at the William Rowan Hamilton Geometry and Topology Workshop, celebrating Martin Bridson’s 60th birthday (July 2025)

Background

In 2013, Hongbin Sun proved that homological torsion is remarkably abundant in finite covers of closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds. Specifically, given a closed, hyperbolic 3-manifold $M$, for every finite abelian group $A$ there exists a finite cover $M’_A$ of $M$ such that $A$ appears as a direct summand of $H_1(M’_A)$. Groves and Chu later extended this result to most finite-volume hyperbolic 3-manifolds with empty or toroidal boundary.

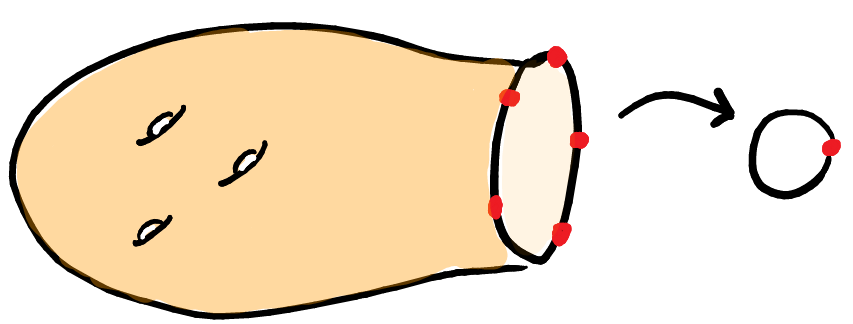

While these results stop short of proving the exponential torsion growth conjecture, they show that the geometry of $M$ can be leveraged to produce a wide range of torsion in the homology of its finite covers. The core of the argument involves immersing 2-complexes $X_p$ (as in the picture) with $H_1(X_p) = \mathbb{Z}^n \oplus \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}$—essentially surfaces with boundary, modified by attaching a $p$-th root of the boundary loops—into $M$, combining them via a ping-pong argument, and then pushing their homology into that of a finite cover via a virtual retraction.

In this project, we investigate whether analogous torsion phenomena arise in a different context: hyperbolic groups that split as graphs of free groups with cyclic edge groups. This class often mirrors behavior found in 3-manifold topology, and here too, we find a strong analogue:

Theorem: Let $G$ be a hyperbolic group that splits as a graph of free groups with cyclic edge groups, and that is not isomorphic to a free product of free and surface groups*. Then for every finite abelian group $M$, there exists a finite-index subgroup $H \le G$ such that $M$ is a direct summand of the abelianization $H^{ab}$ of $H.$

*Note that our assumption on $G$ is crucial, as every finite-index subgroup of a free product of free and surface groups is again of this form, and therefore has a torsion-free abelianisation.

Branched surfaces and homological torsion

The strategy behind our proof diverges quite a bit from the 3-manifold case. There, geometry does much of the work. Here, we lean more on combinatorial counterparts: the structure of graphs, and more importantly, how local data at vertex groups shapes the global behavior of the whole group.

Instead of attaching roots to surfaces with boundary, we use a different model for producing homological torsion: branched surfaces. These are collections of compact, orientable surfaces with boundary, glued together along their boundary components (to form a space that is not a surface). Each (positive genus) surface in a branched surface $B$ defines a relation in abelianization—for example, a surface with boundary components $\sigma_1, \ldots, \sigma_k$ contributes an equation of the form

\[[\sigma] \pm [\sigma_2] \pm \cdots \pm [\sigma_k] = 0\]in the abelianization of $B$. We refer to these as $\partial$-equations. Branched surfaces thus provide a geometric realization of systems of such linear relations.

The first step in our argument is to show that every system of linear equations in a free abelian group is equivalent (in the sense of yielding the same quotient) to one arising from a branched surface. To this end, we show that a simple type of branched surface—three orientable surfaces of positive genus, each with a single boundary component and glued along those boundaries—admits finite covers whose first homology contains arbitrary torsion. We call this a triple branched surface.

Note that branched surfaces are themselves graphs of free groups with cyclic edge groups; the fact that any branched surface has a precover that is a triple branched surface proves the theorem in this case.

Example. Suppose $B$ is a triple branched surface made up of three surfaces $\Sigma$, $\Theta$, and $\Pi$, each with a single boundary circle identified as a common curve $x$. The table below describes a 4-sheeted cover $B’ \to B$ in which $\Sigma$, $\Theta$, and $\Pi$ each lift to two double-sheeted covers, and the common boundary $x$ lifts to four distinct loops $x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4$. This cover has

\[H_1(B') \cong \mathbb{Z}^n \oplus \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}.\]

| $\Sigma_1$ | $\Sigma_2$ | $\Theta_1$ | $\Theta_2$ | $\Pi_1$ | $\Pi_2$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $x_1$ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| $x_2$ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| $x_3$ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| $x_4$ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Indeed, in $H_1(B’)$, we have that $x_i+x_j=0$ for every $i<j\le 4$, which simplifies to $x_1=x_2=x_3=x_4$ and $2\cdot x_1 = 0$.

The general case

Many of the constructions described here are somewhat delicate, often requiring passage to finite covers to address various complications. We gloss over these technicalities here for the sake of clarity.

Having established the result for branched surfaces—and given that hyperbolic graphs of free groups with cyclic edge groups admit local retractions—it now suffices to find a branched surface inside such a group $G$ (as we will see, it is unclear whether this is always possible). This reduces the general case to a geometric problem: constructing a branched surface within $G$. Wilton proved that, unless $G$ is free, it must contain a surface subgroup.

In Wilton’s proof, the non-freeness of $G$ serves as a lower bound on the complexity of vertex links in a graph of spaces decomposition of $G.$ Specifically, if $G$ is not free, then it contains a one-ended graph of free groups with cyclic edge groups, say $G’$, in which—by an old result of Shanitzer—every vertex group is freely indecomposable relative to the incident edge groups. This converts the global non-freeness assumption to a local condition on links of vertices, which allows Wilton to prove:

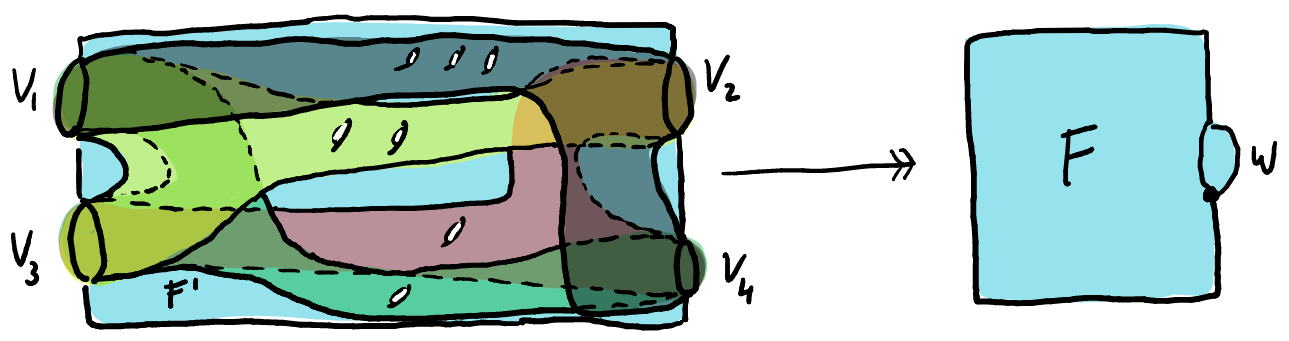

Theorem [Wilton ‘18]: Let $F$ be a free group which is freely indecomposable relative to $w_1,\ldots,w_n \in F$. Then there is a surface with boundary $\Sigma$ and an embedding $f:\pi_1(\Sigma)\hookrightarrow F$ such that

- the image of every component of $\partial(\Sigma)$ is an elevation of some $w_i$ to $f(\pi_1(\Sigma))\le F,$ and

- the total degree of the elevations of $w_i$ to $f(\pi_1(\Sigma))$ is uniform across all $i\le n$.

This is often better explained by means of a pullback diagram:

The above theorem now applies to each vertex group, and the resulting surfaces can be glued together to produce a global surface subgroup inside $G$.

In our setting, the hypothesis that $G$ is not a free product of free and surface groups yields a sharper complexity threshold, which would give one hope to be able to immerse more complicated 2-complexes into $G$ (such as branched surfaces, which are more complex than ordinary surfaces). This complexity bound can manifest in one of two ways:

-

“Triple intersections”. Three distinct cyclic subgroups of $G$ are identified—this creates branching behaviour in the underlying graph, and we can again insert surfaces à la Wilton at each vertex to build a branched surface.

-

Rigid vertices. The cyclic JSJ decomposition of $G$ contains a rigid piece.

The second case is a lot more subtle, and most of our efforts are directed towards it.

Artificial branching

Suppose we are in case 2, so that the underlying graph of $G$ lacks branching behavior, forcing the presence of a rigid vertex. A simple example to keep in mind is the double $F\ast_{w} F$ of a free group $F$ along a complicated word $w$ (for example, one whose Whitehead graph is a complete multigraph with each edge appearing at least twice). Here, the aforementioned splitting of $G$ coincides with its JSJ decomposition (which consists of two rigid vertices), and replacing vertices by surfaces with compatible boundaries yields an honest closed surface, not a branched one (as in the first case).

To navigate this, we construct artificial branching: pieces that simulate branched surface behavior and allow branched surfaces to map to $G.$ The key tool is a theorem of Wilton’s, which shows that rigid vertices satisfy a strong form of one-endedness:

Theorem [Wilton ‘11]: Let $F$ be a free group and let $w_1,\ldots,w_n \in F$ such that $F$ does not split freely or over $\mathbb{Z}$ relative to $w_1,\ldots,w_n$. Then there is a finite-index subgroup $F’\le F$ satisfying the following property:

If $v_1,\ldots,v_k$ are the elevations of $w_1,\ldots,w_n$ to $F’$, then $F’$ is freely indecomposable relative to $v_1,\ldots,v_{i-1},v_{i+1},\ldots,v_k$ for every $i\le k.$

Combining this with Wilton’s construction of surfaces with prescribed boundary in free groups produces many surfaces that embed in $F$ with overlapping boundaries, as illustrated below:

A tempting next step is to replace one copy of $F$ by a surface, and the other by two of these overlapping surfaces (e.g., those with boundary $v_2,v_3,v_4$ and $v_1,v_3,v_4$), creating artificial branching around $v_3$ and $v_4.$ Then, the construction for branched surfaces applies, resulting in $v_3+v_4$ becoming torsion in the abelianization of a finite cover of $G=F\ast_{w} F,$ (or alternatively, a map from a branched surface $B$ to $G$ which induces an injection on $\mathrm{Tor}(B^{ab})\text{).}$

However, this naive replacement is risky. Wilton’s surfaces arise via linear optimization and lack explicit descriptions. Controlling their interaction is subtle, and the candidate torsion element $v_3+v_4$ could conceivably vanish in the abelianization.

To avoid this, we turn to Calegari’s construction of surfaces inside free groups (also known as the rationality theorem for stable commutator length), stated below in a form suited for our needs:

Theorem [Calegari ‘09]: Suppose that $w_1,\ldots,w_n \in F$ satisfy a non-trivial equation

\[\sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i \cdot w_i = 0\]in $F^{ab}.$ Then there is a surface with boundary $\Sigma$ and an embedding $f:\pi_1(\Sigma)\hookrightarrow F$ such that

- the image of every component of $\partial(\Sigma)$ is an elevation of some $w_i$ to $f(\pi_1(\Sigma))\le F,$ and

- for every $i$, if $\lambda_i \ne 0$ then $w_i$ admits a lift which is a boundary component of $f(\Sigma).$

Returning to our setup, if $v_3+v_4=0$ in $F′^{ab},$ Calegari’s theorem guarantees a surface with boundary supported on lifts of $v_3$ and $v_4.$ This enables a minimality argument, choosing surfaces such that no subcollection of their boundary components support the boundary of another surface. In particular, if the surface whose boundary is $v_1,v_3,v_4$ in our example satisfies this property, then $v_3+v_4$ cannot vanish in $F’^{ab}.$ This prevents the artificial branching elements from vanishing in abelianization and completes the proof.